Tony Blair, Withheld Intelligence, and Ireland: What Newly Released Files Reveal — and the Questions They Still Leave Unanswered

The release of previously classified British government documents has reopened a sensitive chapter in Anglo-Irish relations, shedding light on how intelligence was handled and withheld during the premiership of Tony Blair. The files, released under the UK’s archival transfer rules, confirm that Ireland was refused access to UK intelligence concerning potential terrorist threats to the Sellafield nuclear facility in 2004, despite direct representations from the Irish Government.

The disclosure has prompted renewed debate about transparency, intelligence-sharing obligations between neighbouring states, and the broader question of how much information may still be withheld today under the banner of national security.

The Sellafield Context: Why Ireland Was Alarmed

Sellafield, located in Cumbria on England’s northwest coast, has long been a focal point of Irish concern due to its proximity to Ireland and its role in nuclear fuel reprocessing and waste storage. Any serious incident at the facility would have direct environmental and public health consequences for Ireland, particularly the east coast.

Irish concerns intensified following the Madrid train bombings of March 2004, when coordinated Islamist extremist attacks killed 193 people and injured thousands. The attacks demonstrated how infrastructure based terrorism could result in mass casualties across borders.

In this climate, then Taoiseach Bertie Ahern formally wrote to UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, warning that a terrorist attack on Sellafield would constitute a “transnational catastrophe.” Ahern sought access to intelligence assessments so that Ireland could better prepare for any potential fallout affecting its population.

These facts are confirmed in reporting based on newly released UK Cabinet Office and Prime Minister’s Office files, first detailed by The Irish Times following their release to the UK National Archives.

Blair Government’s Decision: Intelligence Not Shared

According to the declassified documents, Tony Blair’s government refused the Irish request. The rationale provided was rooted in long standing intelligence doctrine: the protection of sensitive sources, operational methods, and the integrity of UK security services particularly MI5.

British officials argued that once intelligence was shared externally, even with a close neighbour, there could be “no guarantees” regarding onward access, storage, or exposure. As a compromise, Dublin was told that the British ambassador would inform Irish authorities should any specific and credible threat materialise.

This decision was taken despite Ireland’s repeated objections to Sellafield over safety and environmental concerns and despite the obvious shared risk profile between the two states.

The refusal is now on the historical record.

Not an Isolated Case: Withholding and Redaction in UK Archives

The Sellafield intelligence refusal forms part of a broader pattern of withheld, redacted, or withdrawn UK government files, many of which have emerged through recent archival releases:

Some files released to the National Archives have later been withdrawn or partially suppressed, including documents unrelated to Ireland but raising wider concerns about selective transparency.

Other Blair era records including diplomatic calls and sensitive discussions remain closed or heavily redacted decades later on national security or diplomatic grounds.

Under UK law, files can be withheld indefinitely if deemed damaging to national security, intelligence operations, or international relations. While lawful, this practice means the public record remains incomplete, and scrutiny is limited to what governments decide can safely be disclosed.

Anglo-Irish Intelligence Relations: A History of Asymmetry

Ireland’s experience in 2004 fits into a longer historical narrative of unequal intelligence access between London and Dublin.

Successive Irish governments have argued that British security agencies, particularly MI5, retained information relating to major historical events affecting Ireland, including the 1974 Dublin and Monaghan bombings which was never fully shared with Irish authorities. While those cases fall outside the Blair era files, they underscore a persistent concern within Ireland: that intelligence critical to Irish public safety has often remained beyond Dublin’s reach.

Even within the framework of the Good Friday Agreement and enhanced security cooperation, intelligence sharing has never been equal or automatic.

Security Versus Accountability

From a purely operational perspective, the UK’s decision can be defended on intelligence service grounds. Protection of sources is a cornerstone of counter terrorism work, and governments are often reluctant to widen access to sensitive assessments.

However, from a democratic accountability and public safety perspective, the Sellafield case raises serious issues:

Ireland was being asked to trust assurances without access to underlying intelligence.

Irish emergency planning was constrained by incomplete information.

A nuclear related threat, by its nature, would not respect borders.

This tension between secrecy and shared safety lies at the heart of the controversy.

The Unavoidable Questions: Then and Now

The release of these files forces several uncomfortable but necessary questions into the open:

How much intelligence was withheld from Ireland during the Blair years beyond what is now known?

The archival record is incomplete by design. What remains closed may never be publicly disclosed.

Were decisions to withhold information purely security driven, or were political considerations also at play?

Governments routinely cite national security, but without transparency, such claims cannot be independently assessed.

Has intelligence sharing between the UK and Ireland genuinely improved since 2004 or do similar constraints still apply today?

Modern security cooperation remains largely classified, making it impossible for the public to evaluate whether lessons were learned.

If intelligence was withheld then, how confident can Ireland be that critical information is not being withheld now?

This question is particularly relevant amid contemporary threats, including terrorism, cyber attacks, and infrastructure vulnerabilities.

Conclusion

The newly released Blair era files confirm a hard truth: even close neighbours and partners can be excluded from vital intelligence when national governments prioritise secrecy over transparency. Ireland’s exclusion from detailed threat intelligence relating to Sellafield in 2004 was lawful, deliberate, and strategically justified yet deeply consequential.

As further archives are opened and others remain closed, the balance between national security and democratic accountability will continue to be tested. For Ireland, the episode serves as a reminder that reliance on external assurances carries inherent risks and that unanswered questions from the past continue to shape trust in the present.

Aaron Joyce

Newswire, LTT Media

Newsdesk

30 December 2025

Bertie Ahern

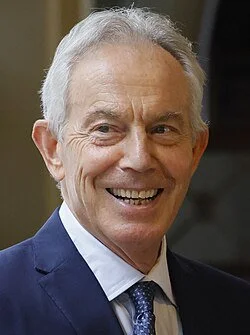

Tony Blair